One of the primary benefits for individuals operating a business under the umbrella of a corporation or limited liability company is avoiding personal liability. As a general matter, “[t]he rule of law that has evolved in New Jersey is that the corporate form as a wholly distinct and separate entity will be upheld.” Coppa v. Taxation Div. Director, 8 N.J. Tax 236, 246 (Tax Ct. 1986). As such, “a primary reason for incorporation is the insulation of shareholders from the liabilities of the corporate enterprise.” State Dep’t of Envtl. Prot. v. Ventron Corp., 94 N.J. 473, 500 (1983).

One of the primary benefits for individuals operating a business under the umbrella of a corporation or limited liability company is avoiding personal liability. As a general matter, “[t]he rule of law that has evolved in New Jersey is that the corporate form as a wholly distinct and separate entity will be upheld.” Coppa v. Taxation Div. Director, 8 N.J. Tax 236, 246 (Tax Ct. 1986). As such, “a primary reason for incorporation is the insulation of shareholders from the liabilities of the corporate enterprise.” State Dep’t of Envtl. Prot. v. Ventron Corp., 94 N.J. 473, 500 (1983).

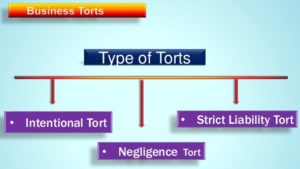

Tort Participation Theory and Intentional Torts

However, New Jersey courts will impose personal liability on a director or officer of a corporation for the corporation’s torts or misdeeds when he or she “commits the tort or . . . directs the tortious act to be done, or participates or cooperates therein, . . . even though liability may also attach to the corporation for tort.” Van Natta Mech. Corp. v. Di Staulo, 277 N.J. Super. 175, 191 (App. Div. 1994) (quoting McGlynn v. Schultz, 95 N.J. Super. 412, 416 (App. Div.), certif. denied, 50 N.J. 409 (1967)).

Known as the “tort participation theory”, this requires the corporate officer to have sufficient involvement in the commission of the tort. Saltiel v. GSI Consultants, Inc., 170 N.J. 297, 3030 (2002). Under the “tort participation theory, liability can attach even if the officer’s acts were performed for the corporation’s benefit and the officer did not personally benefit. Id.

As the New Jersey Supreme Court remarked, New Jersey cases holding corporate officers personally responsible for their tortious conduct generally have involved intentional torts like fraud and conversion. Saltiel v. GSI Consultants, Inc., 170 N.J. 297 (2002). Examples include Charles Bloom & Co. v. Echo Jewelers, 279 N.J. Super. 372, 382 (App. Div. 1995) (defendants could be personally liable for alleged conversion even if they were acting in corporate capacity); Van Dam Egg Co. v. Allendale Farms, 199 N.J. Super. 452, 457 (App. Div. 1985) (declining to dismiss fraud complaint against corporate officer even though it did not allege that he personally benefited from alleged wrongful acts); Robsac Indus., Inc. v. Chartpak, 204 N.J. Super. 149, 156 (App. Div. 1985) (reversing summary judgment for defendant corporate officer charged with malicious interference with contract, fraudulent misrepresentation, and defamation notwithstanding that liability also was imposed on corporation); and McGlynn, supra, 95 N.J. Super. at 417 (finding corporate officers personally liable for knowingly acquiescing in and ratifying alleged conversion).

In a decision decided in 1950, the New Jersey Supreme Court explained the rationale for holding corporate officers personally liable in such cases:

It is well settled by the great weight of authority in this country that the officers of a corporation are personally liable to one whose money or property has been misappropriated or converted by them to the uses of the corporation, although they derived no personal benefit therefrom and acted merely as agents of the corporation. The underlying reason for this rule is that an officer should not be permitted to escape the consequences of his individual wrongdoing by saying that he acted on behalf of a corporation in which he was interested.

Hirsch v. City of Philadelphia, 4 N.J. 408, 416 (1950).

Personal liability may also follow from omissions as well as acts. For instance, in Francis v. United Jersey Bank, 87 N.J. 15 (1981), the New Jersey Supreme Court imposed liability on a director for failing to prevent other directors from taking trust funds from the corporation.

Piercing the Corporate Veil

Another legal theory to impose personal liability on corporate officers and shareholders is known as “piercing the corporate veil”, an equitable doctrine providing redress for an underlying wrong in circumstances where recovery is not otherwise possible because the primary defendant is a business entity without assets to pay a judgment. See Verni v. Harry M. Stevens, Inc., 387 N.J. Super. 160, 199 (App. Div. 2006).

A multitude of factors are evaluated to determine the doctrine’s application, including failure to observe corporate form, under-capitalization and commingling or misuse of corporate funds. The doctrine’s central purpose is “to prevent an independent corporation from being used to defeat the ends of justice, to perpetrate fraud, to accomplish a crime, or otherwise to evade the law.” Ventron, supra, 94 N.J. at 500.

New Jersey Consumer Fraud Act

In certain instances, a statute can impose personal liability against corporate officers. One such statute is the New Jersey Consumer Fraud Act (“CFA”), codified at N.J.S.A. § 56:2-1, et seq. The CFA “is aimed basically at unlawful sales and advertising practices designed to induce consumers to purchase merchandise or real estate.” D’Ercole Sales v. Fruehauf Corp., 206 N.J. Super. 11, 18-19 (App. Div. 1985)(internal citations omitted). (Emphasis added).

The prima facie elements to maintain a CFA claim require a plaintiff to prove: (i) unlawful conduct, (2) an ascertainable loss, and (3) a causal relationship between the unlawful conduct and ascertainable loss.” New Jersey Citizen Action v. Shering-Plough Corp., 367 N.J. Super. 8, 12-13 (App. Div. 2003); see also, N.J.S.A. 56:8-19.

An example of applying the CFA to hold a corporate officer or employee personally liable is Allen v. V & A Bros., 208 N.J. 114, 131, 133-134 (2011). There, the New Jersey Supreme Court held that based on the CFA’s expansive definition of “person” and broad remedial purpose, any corporate officer or employee who commits an affirmative act or knowing omission that violates the CFA, or is responsible for a violation of regulations enacted pursuant to the CFA, can be held individually liable even if it is only the business entity that contracted with the plaintiff consumer.

Conclusion

These and other decisions make clear that despite the personal liability protections afforded by corporations and limited liability companies, individuals acting on behalf of business enterprises remain exposed to personal risk and must act with due care.